|

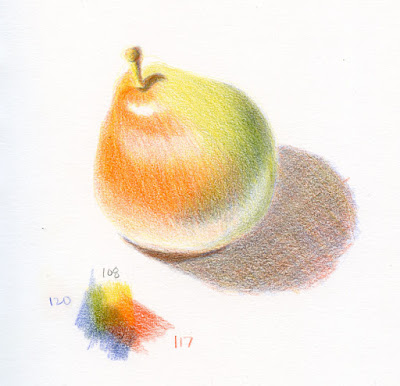

12/20/19 Caran d'Ache Supracolor in Stillman & Birn Beta sketchbook

Scarlet 70 (w), Golden Yellow 20 (w), Ultramarine 140 (w) |

Last week when I posted about my earlier triad experiments, I regretted that I hadn’t

kept track of the specific hues I was using, whether they were warm or cool,

and other useful (or at least interesting) color-mixing details. This time I’ve

documented better and even made mixing swatches next to the sketches so that

individual hues are easier to see.

The

first thing I learned from doing these triad sketches is that I’m not as

confident as I thought I was about identifying cool/warm yellows and blues. I

had a lot of practice identifying and mixing cool and warm hues in the secondary triad palette during my watercolor pencil class a few years ago,

and those seem very straightforward. For example, a warm green has more yellow

in it, and a cool green has more blue. Easy-peasy. Likewise, among the

primaries, a warm red has more yellow in it (and therefore appears red-orange),

and a cool red has more blue in it (magenta).

|

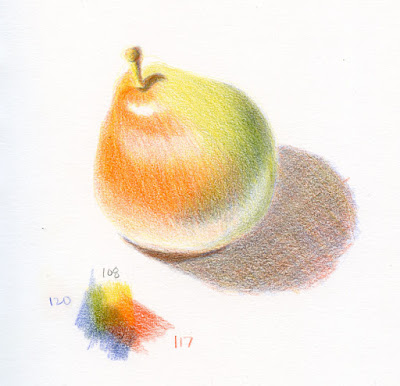

12/18/19 Faber-Castell Polychromos in Stillman & Birn Epsilon sketchbook

Light Cadmium Red 117 (w), Dark Cadmium Yellow 108 (w), Ultramarine 120 (w) |

But

what about yellow (the warmest hue, according to color theory) and blue (the

coolest)? Logically, to make yellow cooler, it would be mixed with blue, but

that would give it a strong greenish hue. In the same way, what is blue mixed

with to make it warmer or cooler? Adding red to blue should warm it up, but the

resulting violet changes the hue significantly.

When

we had discussions about this in class, we learned that one approach to cooling

a hue is to simply mix it with its complement. So, mixing a bit of violet with

yellow would push it toward gray and therefore cool it down. In the same way,

blue could be warmed by mixing it with a touch of orange. This approach is

easier for me.

Why

is it important to understand how to identify cool and warm hues? According to

watercolor books I’ve read, if you stick with either all warms or all cools,

you are much less likely to mix mud. Logically, this makes sense, especially in

view of the complement-mixing discussion: If you were to mix a warm yellow, a

warm blue and a cool red, that cool red is already leaning toward violet, which

would mix with the warm yellow and become grayish-brownish mud. A warm red has

no violet in it, so the mix is likely to be brighter and less muddy. Or so goes

the concept. But I’m here to learn for myself, so in many cases I deliberately

mixed cools and warms.

|

12/19/19 F-C Polychromos, S&B Epsilon

Deep Scarlet 219 (c), Light Yellow Glaze 104 (w), Helio Blue-Reddish 151 (w) |

Of

course, the pigment-mixing color theory (which is the one painters use and that

I learned in class) isn’t the only color theory. Another one says that the three

primaries are cyan, yellow and magenta (plus black, the four hues used in

printing). I’m sure there are other color theories. No wonder it’s confusing!

Anyway,

as I made these sketches, I examined my primary hue options carefully and tried

to identify whether a hue was warm or cool, but I wasn’t always confident in my

choices. Ultimately, I was having so much fun that I didn’t care. I simply

decided, “Hmm, let’s just try it and see what happens.” (The latter attitude is

always faster and easier than caring.)

One

thing to note: As much as I love watercolor pencils for their intensity and

efficiency when sketching on location, I find it much easier to control hues

for this type of exercise with traditional colored pencils. If a color is off,

I can just add more of something to change it; water complicates this process

because many watercolor pencils take on an entirely different hue when water is

applied. In one case, water activation changed a cool, subdued blue in its dry

state to a very bright warm blue. It was apparent in my swatches before

sketching, but I decided to go with it anyway and see what would happen.

|

12/21/19 Cd'A Supracolor in S&B Beta sketchbook

Carmine 80 (c), Golden Ochre 33 (c), Blue permanent 670 (w)

(This blue looks cool and subdued when dry, but when activated,

it appears much brighter and warmer.) |

In

the cutline of each sketch, for my own documentation (and your interest, if any),

I’ve indicated the type of pencil, color numbers and whether I thought they

were warm (w) or cool (c). To simplify my choices, I stayed within a single brand

of pencils for each sketch. In all sketches, I used all three primaries for the

cast shadow and left it dry, even when using watercolor pencils. I enjoy seeing

these optically mixed masses (sort of like the red/green/blue dots making up TV

images that fascinated me when I was a kid).

I

hope you enjoy seeing my varying results. Ultimately, though, looking at my experiments

isn’t nearly as much fun or as informative as doing your own triad studies. On

your next yucky-weather day, whatever medium you use, I recommend making

primary triad studies. You will learn more about your medium as well as about

color.

(As

I write this on the solstice, we’re in our third day of the Pineapple Express.

Gratefully, my car is not submerged in a river of standing water as one was

shown doing on TV news, though our basement had some minor leakage. It’s ideal

weather for making triad studies.)

|

12/21/19 Cd'A Luminance in S&B Epsilon

Alizarin Crimson 589 (c), Lemon Yellow 240 (w), Cobalt Medium Blue 66 (w) |

|

12/21/19 Tombow Irojiten in S&B Epsilon

Cherry Red 1 (c), Mustard 15 (c), Hydrangea Blue 8 (c) |