|

| 11/24/21 Color temperature study; west window view |

One of the studies we did in Sarah Bixler’s color temperature workshop was what I think of as “Rainbow Randy” (see below). The assignment

was to choose about six saturated hues to express a full range of temperatures from

warmest (yellow) to coolest (blue) and the steps in between. We were to avoid

mixing, allowing the saturated hues to do the work of showing the changes in

color temperature.

|

| Rainbow Randy |

No part of Randy’s back was green, yet I could see that the shadow there was slightly warmer than the coolest area behind his neck (farthest from the light). The warmest parts – his face, chest, shoulders – were those that faced the light most directly. The sketch is a garish rainbow, but it very clearly shows where I saw the relative color temperatures.

On yet another gray, colorless morning, I looked out my studio’s west window at the usual view with a new thought: I bet the “rainbow Randy” treatment would have interesting results! The challenge I hadn’t anticipated, though, is that unlike Randy’s neutral-toned skin, the view does have some identifiable local hues, pale and dull as they are. The warmest spot is the yellow house, which is, indeed, yellow (though not nearly as bright as I’ve made it). The house to its right is pale gray, the coolest part of the view, so I made it blue. Those were the easy parts. But what of the trees and other foliage? Now I was confused: They looked varying shades of “green,” but were they warmer or cooler than the dark rooftops I had decided were purple because they were warmer than the coolest gray house?

Suddenly I realized that rainbow Randy was easy by comparison because his complexion has no saturated hues; it’s made of a range of neutral tones. It was becoming increasingly clear to me that a model is an ideal subject for learning color temperature. But I’m determined to figure out how to use color temperature to describe anything I see in the real world (not just life-drawing models) – describe them as well as express them in (I hope) a more interesting way.

With that in mind, I assembled a limited palette of 14 Caran d’Ache Luminance pencils (I’m fickle; I’ll probably choose different pencils next week). The palette is based on a warm and a cool of each of the three primaries (including my favorite CMYK triad, which is checkmarked). Using secondaries in the workshop was more difficult than primaries, so I also included a warm and a cool of each secondary for when I am up for the challenge. The last two are relatively neutral French Grey and Indigo for when I need to lay on the darks.

|

| Limited palette of Caran d'Ache Luminance |

I could have used my usual Museum Aquarelle palette, of course, but the workshop showed me that it’s easier to see how color temperatures work together when the glazing property of transparent (dry) colored pencils results in optical mixing. If I use watercolor pencils, I would be too tempted to mix colors with water instead of learning from the glazing. And in any case, it would be a fun reason to take my non-soluble pencils out in the field, which I rarely do otherwise.

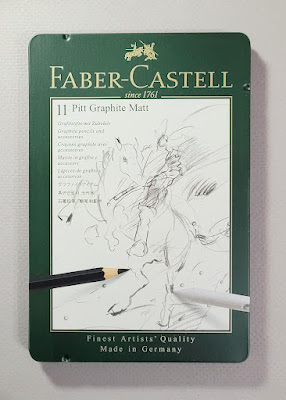

Tomorrow I’ll show you the case I’ll be using to tote this pencil

palette (don’t you love cliffhangers?).

(Hmmm… this turn of events has thrown a wrench into my sketchbook plan. I just filled a Stillman & Birn Beta, and I had been looking forward to starting the Hahnemühle watercolor book I bought a couple of months ago. But I think its tooth is too strong for soft Luminance pencils; I prefer a smoother S&B Zeta with those.)