|

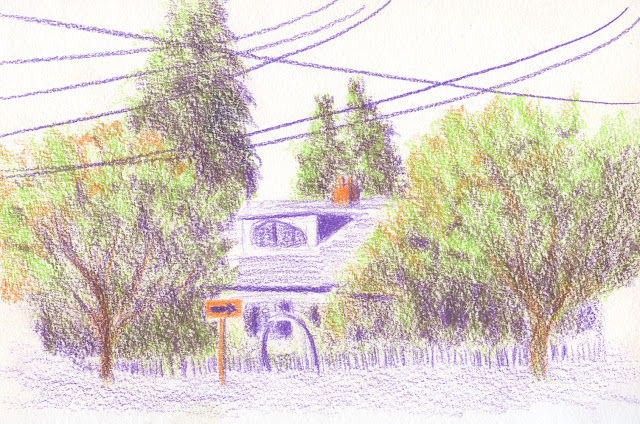

| 9/4/22 Maple Leaf neighborhood |

Some trees are definitely turning. Others have made half-hearted

gestures in that direction but seem reluctant to let summer go. I know that

feeling.

The sketch above shows two varieties of Japanese maples. From a distance, they look like a haze of color, the near one with more green, the one in back with more orange, but both show a full range of hues if you look closely. Some individual leaves display a gradient of hues, while others show only one color per leaf. Thinking about optical color mixing, I realized that these trees are nature’s examples of this concept.

After a couple of blog readers mentioned optical mixing in their comments, I realized that I hadn’t actively talked about this color concept in a while, but my long-time fascination with it continues. I’ve probably been intrigued with optical mixing almost as long as I’ve been using colored pencils, but I always feel like I’m still just learning about how to use it. I know when I’ve done it well, but I might not understand it well enough to explain how I achieved it (or maybe I’m prone to happy accidents). I’m going to try to articulate some thoughts today to see if they make sense.

Here’s a definition of optical mixing that I found in a quick search:

Optical mixing, also known as partitive color, is the perception of color resulting from the combination of adjacent colors. In other words, when color is mixed optically, the blending occurs perceptually, and takes place between our eyes and our brain. The perceived blending of color increases with distance.

A common example that’s often given for optical mixing is

how TV and comic book images are made up of tiny colored dots. In art history, Pointillists and Impressionists are known for their use of optical mixing.

I think reading a how-to book on watercolor years ago was my first introduction to the concept in regard to art making. With watercolor glazing, multiple transparent colors are layered, allowing each layer to dry completely before the next one is applied, so that the color blending occurs only by the viewer’s eye, not by mixing liquid paints. I didn’t get far enough in using watercolors to practice this technique beyond the book exercises, but it helped me to understand the concept.

When I started using colored pencils and especially when I began studying with Suzanne Brooker, my full fascination with optical mixing began. In her first course we used only dry colored pencils, and that’s when I realized how similar they are to watercolor glazing – except easier because all that uncontrollable water stuff wasn’t involved!

2/3/17 Optical mixing was a major component of the large grassy area in this study from Suzanne Brooker's class. The individual colors are lightly applied so that layers underneath stay visible.

11/6/21 In this portrait exercise from Sarah Bixler's

workshop, the facial skin tones and hair are optical mixes

of many pencil colors.

In Sarah Bixler’s color temperature workshops last

year, my intrigue was reignited. Again, using dry colored pencils only, we

explored the subtle shifts of color temperature that can be made with multiple

colored pencil layers. Because most colored pencil hues are transparent and, by

their physical nature, pencil pigments cover only some parts of the paper,

whatever is underneath shows through. Even if a pencil pigment is on the opaque

side, the marks can be made finely so that the effect remains transparent. The

dry pigments don’t blend together the way wet paints do; the eye does the work

of mixing and blending.

When other sketchers realize I use watercolor pencils, they sometimes ask why I am so selective in my use of water. Since water activation makes all watercolor pencil hues more vibrant, why not apply water everywhere?

One compositional reason is that I want to use different degrees of intensity to show depth or to direct the eye. But another reason is that dry pencils can show optical mixing more vibrantly – but only if they remain dry. I’ve made the mistake of drawing an area of pleasing optical mixing, and in my enthusiasm for the achieved mix, I activated it with water to make it more intense. The individual colors are lost, and the result is intense mud.

I still make this mistake occasionally, but here’s an example in which I didn’t: Shown below is a detail from a recent sketch at Green Lake (the one that prompted the reader comments about optical mixing). In those background trees, I used four of my chakra palette pencils in varying degrees. To demonstrate what can happen when water is applied, I tried to replicate the mix in the swatch. I swiped my waterbrush through half of it so that you can see the dark mud that results. When left dry, the individual colors show through subtly, making a complex blend that’s more interesting (and hopefully more visually pleasing) than fully blended mud. In addition, activating with water would have intensified the colors and likely would have brought those distant trees forward. (By contrast, the sunny foreground trees were fully activated.)

Detail of background trees. See below for activated swatch of replicated colors.

When water is applied, the optically mixed colors used

in the trees turn to mud.

In the sketch of the maples at the top of the post, I activated

only the closer tree to bring it forward compared to the one just behind it. (The

difference is subtle, but they were not far apart.) I used all five pencils in

my chakra palette (ahh, all seven chakras were in balance that day!) for each

tree, but in varying amounts and degrees of intensity. I used enough colors

that a heavy-handed application of water with a brush could have turned the

front tree muddy, but I kept the spritzing minimal. The Hahnemühle sketchbook’s cold-press texture did the work of giving my sketch a bit of

the Pointillist effect even on the tree that I activated with water. Often that

texture gets obliterated when a brush is used, which is why I favor spritzing

when I want to retain some texture.

In the secondary triad sketch I made last spring (below), I used non-soluble pencils, so I couldn’t have made wet mud even if I’d wanted to. I know that it’s still possible to make dry mud, especially with a secondary triad, but I hope that optical mixing allows the individual colors to shine through while avoiding mud.

|

| 4/28/22 Optically mixed secondary triad colors |

Other examples shown in this post are explained in the cutlines.

I hope I’ve been articulate, but even if I haven’t, trying to talk about all this has excited me about optical mixing all over again! I’m looking forward to giving these concepts and techniques a solid workout this fall with a secondary triad palette.

|

| 6/14/22 In this rooftop detail of a sketch I posted on June 18, I used color temperature to subtly indicate the side that had more light and optical mixing of pencils left dry. |

|

12/4/21 This still life, which was a color temperature exercise, was made with the CMYK primary triad shown in the upper-right corner. The avocado shows an interesting example of optical mixing of only the three hues. Although the Stillman & Birn Zeta paper I used is relatively smooth, it has enough texture to bring out the pixelated or Pointillist effect that enhances optical mixing.